By Ángel Mendiola Ross, Sarah Treuhaft, Michelle Huang, Justin Scoggins, and Kimi Lee of Bay Rising*

With so much attention focused on the 2020 presidential elections, it is easy to forget the importance of local elections to the everyday lives of Bay Area residents. Local governments are the closest and most responsive to the people. They also make critical decisions around issues like housing, policing, and transportation that can have significant equity implications – for example, the racist and unconstitutional “stop and frisk” policing policies of the recent past.

Given the power instilled in local electeds, it is crucial that these leaders reflect the diversity of the communities they represent. Although race or gender do not alone determine whether an elected official will advance racial or gender justice, and having more people of color and women in office does not automatically translate to more equitable policies – representation matters. Leaders who come from communities that experience discrimination and structural racism firsthand bring that knowledge into governing and can be important advocates for policies that dismantle barriers and improve conditions. And when marginalized communities gain representation in the halls of power, they can feel less neglected, gain trust in government, and have a stronger sense of belonging.

This is why the Bay Area Equity Atlas includes the diversity of electeds as a key metric for tracking equity in the region. To examine how well the Bay Area’s top elected officials represent the diversity of the region’s population, we assembled a unique dataset on the race, ethnicity, and gender of the mayors and council members of the region’s 101 municipalities, and the county supervisors and district attorneys for the region’s nine counties.(1) Our dataset captures the composition of elected officials at three points in time to cover the results of 2017-2019 elections.

This analysis presents new data from two election cycles: November 2018, when 160 local elected positions were up for grabs, and November 2019, when 10 positions were open. The longitudinal data allows us to update previous data from May 2018 to examine whether we are making progress on this important indicator.

Our key findings include:

- While the region is 60 percent people of color, whites hold 71 percent of local elected offices.

- There are dozens of cities without any Black, Latinx, or Asian and Pacific Islander (API) representatives at all: among the 101 municipalities within the Bay Area region, 80 have zero Black elected officials, 42 have zero Latinx or API elected officials, and 33 have all White elected officials.

- The share of women holding office in top municipal and county level positions is now 44 percent — up from 40 percent in May 2018; however among Latinx electeds only 40 percent are women.

- APIs and Latinx people continue to be sorely underrepresented among local electeds, especially at the county level. Latinx and APIs make up half of the region’s population but are just 13 percent of top county-level elected officials. Most strikingly, Santa Clara County has the largest share of API residents of all the nine counties that make up the Bay Area (35 percent), but there are no API electeds in top county positions. Similarly, in Sonoma County, which is 26 percent Latinx, there are no Latinx in top county elected positions.

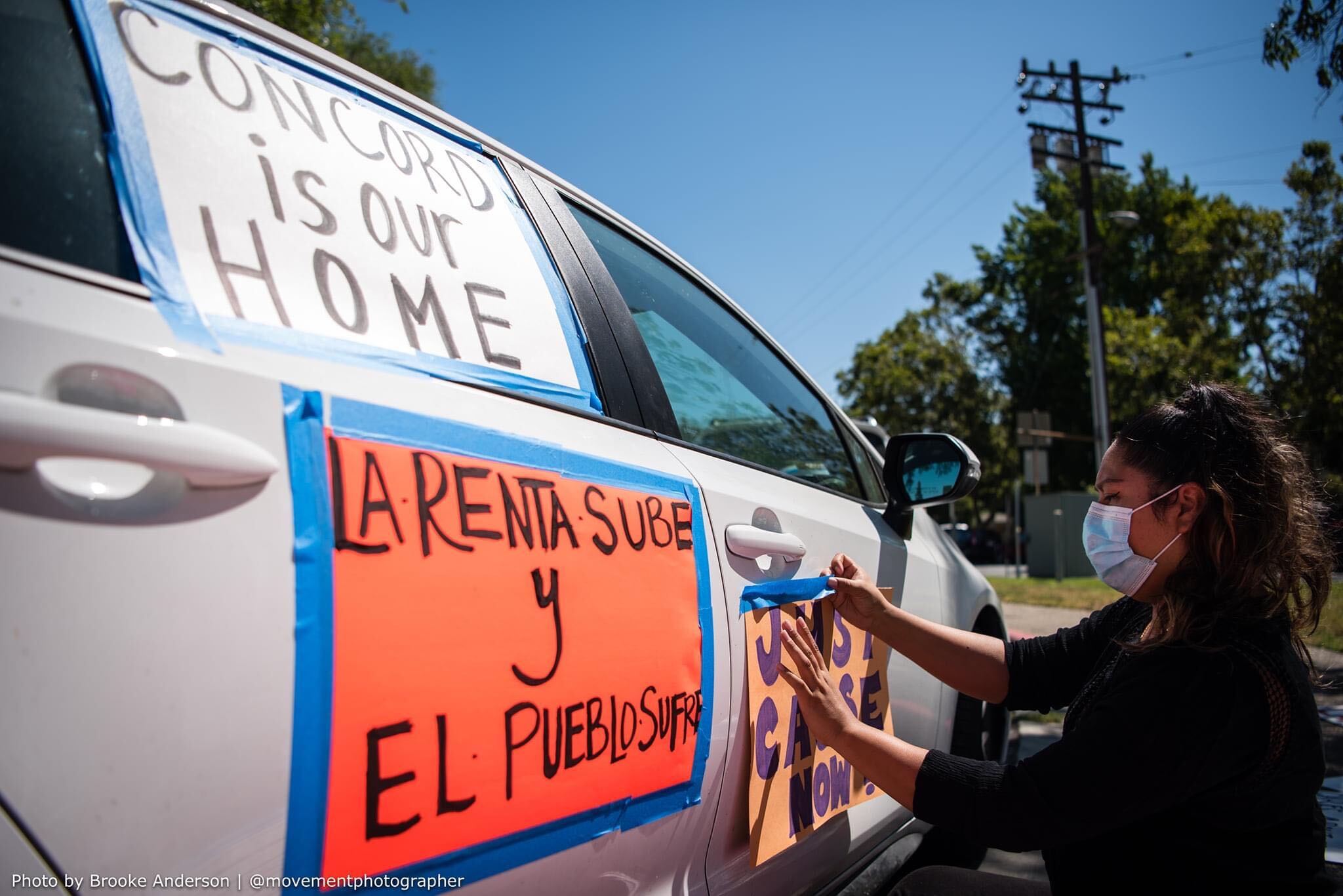

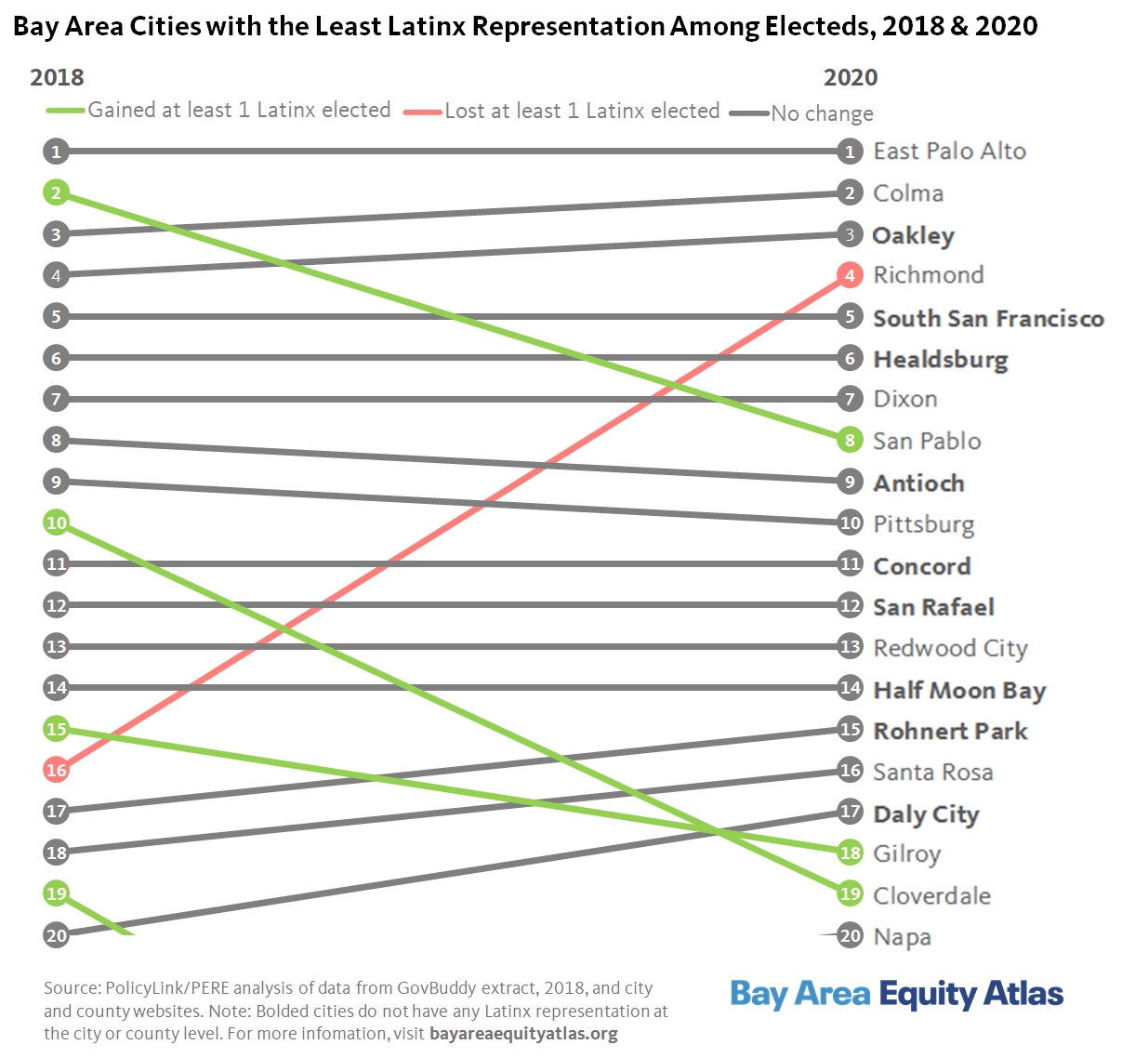

- The most substantial changes in representation since the 2018 elections were at the city level, including several shifts in the rankings of the cities with the largest White overrepresentation and Latinx, API, and Black underrepresentation. Five cities that were formerly represented by all-White city councils elected at least one person of color in 2018: Benicia, Brisbane, Cloverdale, San Ramon, and Santa Clara.

Despite notable wins for candidates of color in the last couple years, the region continues to underperform on this equity metric. Campaign finance and election reforms and investments in programs that support people of color in running for elected office as well as increased voter engagement efforts are all needed to ensure that the region’s diversity is truly reflected in local elected offices.

Regionwide, Whites Remain Overrepresented with Some Progress After 2018 Elections

In early 2018, 74 percent of elected officials were White. But by 2020, the share of White elected officials in the region decreased to 71 percent. Whites are still overrepresented among local elected officials as just 40 percent of the region’s population is White, but the 2018 and 2019 elections made some progress toward reducing this overrepresentation. The slight uptick among people of color was due to increases in Latinx, Black, and multiracial elected officials.

Despite comprising 26 percent of the region’s population, only 10 percent of local elected officials identify as API. Similarly, 24 percent of residents are Latinx, but only 10 percent of local elected officials. As of early 2020, there is still not a single top city or county elected official in the Bay Area who identifies only as Native American. Across the region, there are 65 cities that do not have a single Latinx councilmember and 63 cities without any API representation.

Number of Women in Local Elected Office Increased by 31, But White Men Still Overrepresented

Reports of a record-breaking number of women running for office in 2018 led many to dub it the “Year of the Woman.” White men are particularly overrepresented among local elected officials, but there were significant changes in gender disparities after the November 2018 elections. In the Bay Area, the number of women in top local elected positions increased by 31 from 236 to 267. In early 2018, 60 percent of White electeds were male. But that share declined to 56 percent after the 2018 elections.

But not all racial/ethnic groups saw progress toward greater gender representativeness. The most gender parity is among API electeds, 49 percent of whom are women. The gender disparity remains largest among the Latinx population: just 40 percent of the region’s Latinx elected officials are women. And whereas Black elected officials were previously the only group of electeds in which women outnumbered men, that changed with the 2018 election. Before the election, 18 of the region’s 33 Black elected officials were women (55 percent). Today, just 17 of the region’s 39 Black elected officials are women (44 percent).

By 2020, four Bay Area cities were represented entirely by men: Woodside, Dixon, Corte Madera, and Richmond. The councils of Woodside and Corte Madera are the only ones made up entirely of White men. Los Altos, on the other hand, is the only city in the region represented by an all-female city council.

Underrepresentation of Asian and Latinx Residents Especially Pronounced at the County Level

Underrepresentation of API and Latinx residents is especially pronounced among county-level officials: just four of the region’s 60 county-level officials are API and four are Latinx. Put another way, Latinxs and APIs together make up half of the region’s population but are only 13 percent of top county-level elected officials. Among the region’s nine district attorneys (DAs), all except for one are White, and none are API or Latinx.

Most strikingly, Santa Clara County, which has the largest share of API residents among the nine Bay Area counties (35 percent of residents are API), has no API electeds in top county positions. Alameda County has one API supervisor (out of five) but 30 percent of the county’s population is API. The San Francisco Board of Supervisors has three API members, but APIs are still underrepresented as these three electeds make up just a quarter of top elected officials in a county that is 34 percent API.

Only Napa, Santa Clara, and Solano Counties have any Latinx supervisors. Latinxs in Napa County are most evenly represented: the county has two Latinx supervisors (making up 33 percent of top county elected officials) in a county that is 34 percent Latinx. Santa Clara and Solano counties each have one Latinx county supervisor (out of five) even though Latinxs make up just over a quarter of the population of both counties. In Sonoma County, which is also a quarter Latinx, there are no Latinxs in top county elected positions.

Whites, on the other hand, are severely overrepresented in county-level elected positions. In three counties (San Mateo, Sonoma, and Marin), the entire Board of Supervisors (plus the DA) are White even though White people make up 40 percent of San Mateo County, 64 percent of Sonoma County, and 71 percent of Marin County. In Santa Clara and Solano counties, where more than 60 percent of the population are people of color, all but one of the top county officials are White. The only non-White DA in the whole region is Diana Becton in Contra Costa County.

Despite Notable Victories for Candidates of Color, Whites Still Overrepresented in City Councils

The most substantial changes in political representation were at the city level, including several shifts in the cities with the largest White overrepresentation and the greatest Latinx, API, and Black underrepresentation.

As of February 2020, 33 Bay Area cities are represented by all-White city councils — down from 36 before the 2018 elections. Five cities that were formerly represented by all-White city councils elected at least one person of color in 2018 or 2019: Benicia, Brisbane, Cloverdale, San Ramon, and Santa Clara. But three city councils turned all White, losing one elected of color: Moraga, Rohnert Park, and Larkspur. This means that, in a region of 7.8 million people, nearly 330,000 people of color live in cities or towns that lack elected officials of color to represent their interests. Most notably, Albany is one of those 33 cities even though its population is majority people of color. Campbell, Napa, Pacifica, Pleasanton, and Vacaville are also less than 55 percent White, but as of this year, are represented by all-White city councils.

The cities most overrepresented by White electeds are largely the same group of South Bay cities from before the 2018 elections. Notably, the cities of Santa Clara and Sunnyvale each elected one API council member in the 2018 election. Santa Clara elected a South Asian (immigrant) city council member (Raj Chahal in District 2) and Sunnyvale elected a Chinese American city council member (Mason Fong in Seat 3 who is believed to be the youngest person ever elected to the council at 27 years old), but Whites are still severely overrepresented on both councils (accounting for six out of seven members) in cities that are only 33 percent White. Across the Bay, the city of San Ramon also elected a woman of color to the council in 2018. The city is only 39 percent White, but four out of five city council members are White. Only three cities in the entire region (East Palo Alto, Milpitas, and Pittsburg) do not have any White representation on their city councils.

The city of Fremont made progress on increasing political representation for its API population. In 2018, the Fremont City Council expanded from five to seven members and had their first ever district elections. The number of API city council members doubled from two to four, including two men and two women. In fact, Fremont now has the most API council members of any Bay Area city and is evenly represented as APIs make up 58 percent of Fremont’s population.

As API representation among elected officials did not shift considerably regionwide, a few cities remain severely underrepresented. In Western Contra Costa, for example, the city of Hercules is nearly majority (48 percent) API but only the mayor is API. Similarly, the city of Pinole is 25 percent API but not a single city council member is API.

The North Bay city of Cloverdale improved its representativeness for its Latinx population, which is 31 percent of the total city population, by electing a Latinx to the city council in 2018. In fact, Council Member Marta Cruz cited the fact that Cloverdale had no Latinx representation on the city council or school board as a reason for her running.

In 2020, there were still six cities across four counties (Oakley, South San Francisco, Healdsburg, Antioch, Concord, and San Rafael) with populations between 30 to 35 percent Latinx without a single Latinx local elected official (at either the city or county level).

Of all 101 cities in the Bay Area, just 21 have at least one Black city council member or mayor (up from 19 cities before the 2018 elections). The Eastern Contra Costa County city of Pittsburg has more Black representation than any other Bay Area city. Four out of the five council members are Black, two of whom are Black women. Richmond also has four Black city council members (out of 7 overall), all of whom are Black men.

Richmond contrasts with the city of Vallejo. Both cities are 20 percent Black, but before 2018, there were no Black city councilors in Vallejo. During the 2018 election, Hakeem Brown received the most votes out of any of the five candidates in the race. But with just one Black member out of seven total seats, Black residents in Vallejo remain underrepresented.

Eighty cities and towns across the Bay Area do not have a single Black city council member, including Emeryville (which is 15 percent Black), San Pablo, and San Leandro. Notably, both San Pablo and San Leandro each lost a Black city council member after the 2018 elections.

Looking Forward: Toward A More Inclusive Bay Area Politics

Despite notable improvement since 2018, the Bay Area still lags behind when it comes to political representation – hindering the inclusive, multiracial, community-driven political coalition needed to solve our region’s challenges. As the Bay Area continues to grow in diversity and APIs and Latinxs comprise a growing majority of the population, greater inclusion in local government is critical to responsive and democratic governance. Continuing to cultivate the region’s Black leadership at the city and county levels will also be essential to realizing a more just region – including as a strategy to counter the trend of Black displacement.

Improving on this measure will require addressing the multitude of barriers that prevent more people of color from running for office. With so few people of color in elected positions, young people of color have little legacy of electoral leadership, or elders teaching them why it matters and how to do it. For some immigrants who came to this country after living in military dictatorships and other oppressive government regimes, there is trauma associated with elections and rampant corruption. Language access continues to present a barrier, and many immigrant families are focusing intensively on work and education, leaving little time for political involvement. Working class people in the region are already stretched to make rent, find affordable childcare, and secure living-wage jobs.

Myriad institutional barriers hinder people of color from getting involved in government elections. Over the last few years, wealthy donors have invested hundreds of thousands of dollars into local races, making it very difficult for someone without private wealth to successfully run a campaign. Lack of adequate translation or interpretation for non-English speakers makes it difficult to fully comprehend what is on the ballot or what is being proposed. Black and Brown people have been the target of the criminal justice system, with over policing and high rates of incarceration, which also pushes their communities away from political engagement. The displacement crisis in the region also deters involvement: people who are housing insecure or who are new to an area are not inclined to run for office. Lack of access to childcare makes it harder for mothers to find time to run. Childcare as a campaign expense is a new concept and was just recently approved as an allowable expense. In addition, lifelong politicians and political parties serve as gatekeepers and often choose their successors rather than supporting grassroots leaders connected to community organizations.

Bay Area funders and policymakers must address these barriers and advance policy changes and programs that result in more candidates from underrepresented communities getting elected to city and county elected offices, especially in communities where people of color are severely underrepresented. The Bay Area Equity Atlas and Bay Rising offer the following recommendations:

- Local city and county governments should pass structural reforms including public campaign financing and campaign finance reform to curtail corporate contributions, secret Super PACs, and “pay-to-play” politics — and should consider shifting from at-large to district-based elections. There has been some adoption of these strategies in the region: San Francisco, Richmond, and Berkeley have public campaign financing, and Oakland has some limited public funding available, but more localities need to adopt public financing and make reforms to ensure that the resources these programs offer are enough to make a difference. San Jose is considering a 2020 ballot measure to increase disclosures of large campaign donations and limit contributions from people and companies with land-use decisions before the city, and San Francisco passed such a measure in 2019. Additionally, more than a half-dozen Bay Area cities have recently moved to district-based elections. This shift may support the election of people from underrepresented backgrounds, as the case of Fremont shows, but more time is needed to determine their effectiveness.

- Local and national philanthropies and corporations should fund equity-oriented leadership development programs that prepare people from underrepresented communities of color to effectively engage in public policy. Urban Habitat’s Boards and Commissions Leadership Institute — which has been replicated in several cities — and Bay Rising’s leadership trainings exemplify the type of programs that funders should support.

- Funders, political leaders, and donors should invest in training and support systems for candidates from underrepresented communities to run electoral campaigns as well as community-based programs that support new elected officials from underrepresented communities once they are in office. People active in conventional political parties should work in partnership with community organizations to recruit, train, and support candidates from underrepresented communities to run successfully at all levels of government.

- Policymakers and funders should support voting reforms and civic engagement efforts that increase voter registration and turnout among underrepresented communities, especially in local elections. Reforms, including efforts to increase language access, allow noncitizens to vote in local elections, and lower the voting age to 16, are gaining attention in the Bay Area. San Francisco now allows non-citizen parents to vote in school board elections, and in November 2020, voters in the city will also have the chance to decide whether to lower the voting age to 16 for local elections. What’s more, San Jose is considering a move to align their mayoral elections to presidential election years to increase turnout, especially among underrepresented communities.

* Kimi Lee, director of Bay Rising, serves on the Equity Campaign Leaders Advisory Committee of the Bay Area Equity Atlas. Bay Rising is the only regional civic engagement organization that organizes with working-class people and people of color as voters in the Bay Area year-round. Bay Rising is the umbrella network for San Francisco Rising, Oakland Rising, and Silicon Valley Rising, and represents over thirty grassroots organizations in the Bay Area.

1 We use “city” interchangeably with “municipality” for brevity. In this analysis, “city” also includes towns. Using the May 2018 list of elected officials provided by GovBuddy, we identified the race and gender of the elected officials via web-based research. We then sent the information to the elected officials via email and mail, providing them with multiple opportunities to correct the data. We updated this list using aJuly 2019 GovBuddy list and elected officials after the November 2019 elections were identified based on the last month and year of the elected position’s term. This methodology enables the collection of broad racial/ethnic and gender categories, but not detailed ones (e.g. specific Asian or Pacific Islander subgroups, non-binary gender identification). To assess representativeness, we calculate the difference between the share of that group among top elected officials and the share of that group in the total population. For example, if 60 percent of a city’s population is Latinx but only 20 percent of electeds are Latinx, the Latinx population is underrepresented by 40 percentage points (20 percent minus 60 percent = -40 percentage points). Note that in this analysis we focus on notable shifts for city-elected positions, while on the Atlas the data for cities includes both city council and county elected officials (supervisors and DAs) because county elected officials also represent the residents of the municipalities in those respective counties. See our full methodology here.